Aronofsky’s film follows a search for an unknown quantity, the 216-digit constant in the equation of the universe. Max, like von Neumann, is looking for the key to the stock market. Unlike the science of game theory, the approach is through mathematics—he doesn’t want a theory, he wants an equation with the ability to exactly predict the movements and fluctuations of the stock market. Max believes that the stock market, as a system, operates organically, and understanding this microcosmic process will open up the logic of the universe.

Like Baudriallard says, “there is nothing worse than to utter a wish and to have it literally fulfilled” (152).

Max’s donor is Euclid, his computer; Max and Euclid both operate on a formal etiquette, an exchange of language, that of mathematics. Euclid is like the Tit-For-Tat program in Prisoner’s Dilemma: it can only communicate through its actions. Sol and Max can communicate to each other through language and math, but Euclid only communicates through math. Max proves himself worthy through his manipulation of formal systems; Max’s benefactor is a machine because Max is a virtuoso of machine language.

We can see this better in contrast. Max is not a social being; his interactions with other people are typically standoffish, even abusive. Max has his neighbor, Devi, as a social donor, though after Max throws her out of his apartment, she disappears from the narrative. He insults her, violates etiquette, just as he does with Sol, who also exits the narrative following a quarrel with Max. Max is better with machines than with humans; none of the people in the story become Max’s donor because he has very little regard for symbolic and contractual relationships. These characters do compete for Max, like potential donors—they each try to offer something to Max that will aid him. Marcy and Lenny become violent, seem like antagonists, but this is too superficial; this is simply the nature of Max’s sociality. Sol, Marcy, Lenny seem like competing donors; calling Marcy and Lenny antagonists seems overtly superficial. It seems more likely the number is the antagonist—but it is also the gift object of symbolic exchange.

Euclid “spits out” the number near the start of the film. The number accumulates value as it circulates amongst the characters: Sol confirms the significance of the number, Marcy verifies its efficacy when her attempts to deploy it cause a stock market crash (which Euclid predicts, showing that the number is self-aware and capable of accounting for its own influence), Lenny and the Hasidic Jews elevate the number to the spiritual realm and grant it transcendence as the true name of God (Max secularizes and immanentizes the transcendent qualities, abstracts the pure science from the economic applications; for him, the number is the key to understanding the chaos of nature and creation).

But the gift is also the source of accidents. It is the product of an accident—Euclid crashes immediately after printing the number. Sol thinks that this number allows computers to become self-aware, but only briefly, because this knowledge is fatal—a formal system cannot handle functioning at that level.

Max doesn’t fare much better. The number seems woven into Max’s unconscious—he’s capable of using it, but never articulates exactly how to use the number. Marcy and Lenny can’t do it, at least not properly—that’s why they need Max (and in this sense, the potential-donor relationship inverts). Max’s comprehension of the number is a bit like saying that the human brain does a sort of natural calculus: when a baseball player dives for a ball, his brain naturally ‘calculates’, accounts for all the variables of the situation, and the player ends up with a solution that will put the ball firmly in his glove. But a ball player couldn’t tell you how to do all those calculations—it comes naturally. Max, once he’s comprehended the number’s value, performs this sort of mental math that allows him to see the hidden patterns.

Fiona Apple : (aside) “If there were a better way to go then it would find me /… Be kind to me or treat me mean / I’ll make the most of it”. Max is an extraordinary machine.

But Max eventually begins to break down. His brain can’t handle this function; it exacerbates an existing mental condition caused by staring at the sun as a child—staring at the number too long has the same disastrous effect. Sol suffers the same fate—he retired from his work after a stroke, and when he returns to it after his fight with Max, he shares Euclid’s fate.

It’s not about the number, but knowing how to use it. Marcy attempted to use the number to play the market, resulting in financial disaster. She knows the number, but Max understands it. Max says that the key is not the number, but its “meaning, syntax”. The Jews have an inappropriate hermeneutic—transcendence isn’t the answer. “You’ve calculated every 216 digit number, you’ve intoned all of them, what has it gotten you?” Utility isn’t the answer either—Marcy crashes the stock market when trying to control it. The pursuit of pure understanding leads only to non-comprehension.

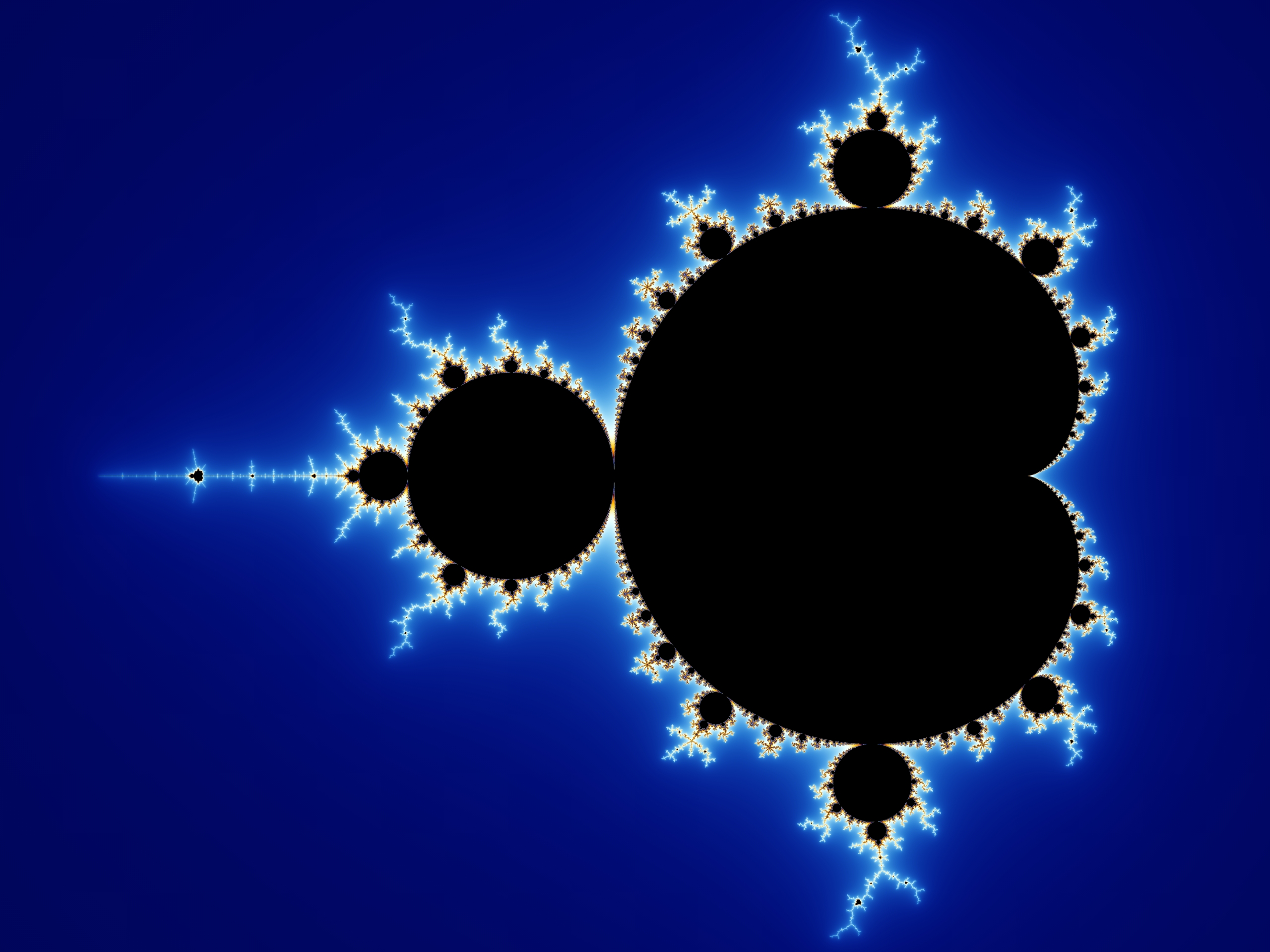

Max and Sol try to accommodate a formal system, while Euclid attempts to accommodate a removal from that system, an awareness of itself as constituted by the workings of its own formal system. The only solution is to unknow quantity. Sol and Euclid auto-terminate; Max self-trephinates, structurally deprives himself of the ability to deal with numbers, and is left only with the expression of the grand equation: the surface aesthetics of the natural pattern, that which arises from the numbers but is not the thing itself.

The universe as a fractal organic system. The price for perfect knowledge, however, is disaster—pain, madness, fatality—for Max and the system, the stock market. Euclid’s self-awareness gives us an insight object-cognition in the midst of an accident: that is, how does the object experience the disaster? What is the object’s point of view? In this case, how does the mechanical, the purely formal, react to the organic and irrational? It self-destructs. (So does the organic when experiencing the pure insight of perfect mechanical logic—poor Max.)

The mechanical is purely formal, but the organic is irrational. The organic circle, an undifferentiated unbounded curve defined by an irrational constant— π.